Empowering people with MS through transparent health communication

30.11.2022Guest Blog Post by Aleksandar Ninkov, a young person with MS from Serbia, board member of MS Platforma Srbije on empowering people with MS through transparent health communication.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) patients are facing a series of difficult questions about probabilities related to their diagnosis. What is the effectiveness of different kinds of MS treatments? What are their side effects? What if they do not take a disease-modifying treatment at all? One of the possible solutions to these ambiguities is to leave MS-related decisions to a neurologist. However, although a neurologist is an expert in keeping multiple sclerosis under control, only MS patients know their own preferences and values that should be taken into account when considering a course of action. The importance of informed patients, capable of making decisions together with their doctors, is therefore emphasized more and more often.

Health communication and understanding

One of the biggest threats to health communication is the fact that many people do not understand health-related statistical figures. For example, there is evidence that MS patients’ understanding of treatment risks and benefits is often unsatisfactory [1]. Furthermore, widespread problems with low statistical numeracy skills can compromise peoples’ comprehension of health information [2]. A low understanding of medical statistics could thus present a serious barrier to patients’ involvement in health decisions.

However, what if the problem is not (only) in patients but in health communication? MS patients may not all be experts in statistics, but there are ways to present health information more or less transparently and intuitively. Professor Gerd Gigerenzer and colleagues illustrated the impact of the non-intuitive and non-transparent health communication by showing that people actually had more inaccurate estimates of cervical cancer risk after reading a certain cervical cancer leaflet [3]. The leaflet presented the number of cervical cancer cases per year without any reference class, i.e., without specifying what was the size of the population the number of cancer cases refers to. For example, information that 3 persons die of cancer each year can present a serious risk if it is 3 cases in 100 persons or a small risk if it is 3 cases in 10 million people.

When it comes to my experience with MS-related health communication, I often see social media posts and news that try to persuade rather than inform. The impression is that MS medication opponents in Serbia are especially skillful in using communication skills and techniques for convincing people. This could in turn lead to even more misunderstanding of MS-related health information.

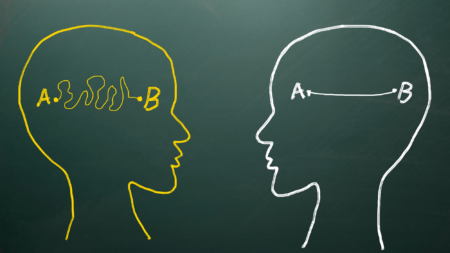

In summary, the same health information can often be framed differently and the choice of the presentation can affect peoples’ understanding, emotions, and decisions. Nonetheless, health communicators such as the media sometimes present health statistics in a biased and non-intuitive way [4]. Two strategies for enhancing medical statistics understanding via adequate presentations will be discussed in the sections below.

How bad is a 100% risk increase? Absolute versus relative risks

Imagine a hypothetical situation where you have the opportunity to switch to a new and more effective treatment for your health condition. However, you find out that the risk of side effects is 100% higher with the new treatment compared to the current treatment. 100% risk increase certainly sounds frightening, but what does it actually mean? This example shows relative risk presentation, i.e., the change in risk compared to the current treatment. But risks can also be presented in absolute terms, i.e., by showing the likelihood of side effects for the two treatments.

Imagine now that you also find out the absolute risks: one person in 100 suffers side effects with the current treatment, while two people in 100 experience side effects with the new treatment. Therefore, the absolute risk increase is from 1% (one person) to 2% (two people). The risk of a new treatment now seems less scary compared to the “100% risk increase” information. Note that relative and absolute risk presentations are in agreement here: an increase from one to two persons suffering side effects is a 100% risk increase. In other words, both relative and absolute risks are correct. However, relative risks make changes in risk appear larger. When it comes to MS, there is evidence that presenting absolute risks increases MS patients’ understanding of the likelihood of treatment side effects compared to presenting relative risks [5].

One in a hundred or 1%? Frequencies versus percentages

The previous scenario also showed the two ways in which probabilities can be presented. We can say that side effects of a certain treatment occur in 1% of cases or 1 out of 100 cases. Note again that both the percentage and frequency of presentations are correct: 1% of patients is 1 out of 100 patients. However, just like in the case of relative versus absolute risks, percentages and frequencies can have different impacts on understanding. Percentages are a more abstract way of presenting probabilities. On the other side, frequencies can be better at fostering comprehension because they are more intuitive. For example, Gerd Gigerenzer showed that much of the confusion regarding probabilities are eliminated when using natural frequencies instead of percentages. Concerning MS patients, using frequencies to present the risks and benefits of treatments can be a good choice for enhancing the understanding of treatment-related probabilities [7].

Empowering through information

Improving statistical literacy through education is certainly a significant goal worth pursuing, but a lot of misunderstanding and confusion also arises due to inadequate health statistics communication. Therefore, if MS patients do not fully understand MS-related statistics, they could ask themselves the following before giving up on grasping the figures: “Is MS information communicated to me intuitively and transparently?” On the other side, health communicators such as the media and organizations should not focus only on the correctness of health information but also on the way the information is presented. These strategies would support the principle of shared decision-making in healthcare, where the patients’ autonomy and preferences are fully respected in the decision-making process, putting the patient at the center of MS care.

Your Account

Your Account