How Brain Imaging and Motion Sensors Are Unlocking Potential For Personalised MS Rehabilitation

10.11.2025For many people living with multiple sclerosis, walking becomes increasingly difficult over prolonged periods due to a phenomenon called “walking fatigability”—a measurable decline in walking ability that goes beyond ordinary tiredness. Felipe Balistieri Santinelli, a PhD candidate at Hasselt University in Belgium, is using motion sensors, gait analysis, and brain imaging to understand why this happens and how it varies from person to person. His goal: to develop personalised rehabilitation programs that address each individual’s specific walking challenges, helping people with MS maintain their mobility and independence.

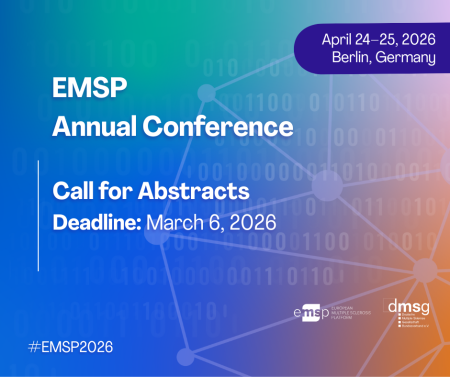

Felipe is also a member of EMSP’s Young People Network (YPN), a community for people under 35 living with MS, NMO, and MOGAD. EMSP spoke with him to learn more about his research and its implications for MS rehabilitation.

What does “walking fatigability” mean in everyday terms? How is it different from just feeling tired?

When we talk about fatigability, in general, there are two forms: perceived and objective. While the perceived fatigability is the increase in the perception of effort induced by a task, objective fatigability is more related to the motor or cognitive performance in a task as well. Surprisingly, these two concepts are not related. Therefore, feeling tired does not necessarily mean your motor or cognitive performance is being affected to the same magnitude as your feeling of effort or tiredness.

For walking fatigability, we can define it as a decrease in walking speed or the appearance of some impairment in gait quality when one has to walk for prolonged periods. In other words, is a decrement in walking performance over time. Again, the increase in the feeling of tiredness occurs independently or is very little related to the worsening in walking.

Some people with MS experience a slowdown in walking speed, while others show changes in their walking pattern or stability instead. What does this tell us about how MS affects different people, and why is it important to recognise these differences?

Actually, this confirms what everyone knows about MS: a very heterogeneous disease in every aspect, including walking fatigability. In our research, we have found that the way walking fatigability manifests differs a lot from patient to patient. The importance of recognising and finding these different manifestations is in the elaboration of the rehabilitation program, where for each patient, a personalised program has to be made to address their own problem.

Your research uses some fascinating technology—sensors, motion analysis systems, and brain imaging during walking. Can you walk us through what a typical study session looks like for a participant? What are you actually measuring?

We indeed use different technologies to understand different aspects of the motor behaviour of people with multiple sclerosis. Normally, a study session takes about 1 hour and 30 minutes, where we perform questionnaires, clinical and walking tests. The session is thought to not take very long, but also give enough time for recovery from test to test to minimise possible fatigue accumulation problems. Specifically, we use inertial measurement units (sensors) to measure the movement quality. This is extremely important and gives us advantages to find small issues that might not be visible in more simplistic measurements, such as measuring only walking speed. For brain imaging, we have at our facilities an equipment called “functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS)”. The fNIRS is a mobile equipment, which means we can use it to measure in real time cortical brain activation while people move or walk. It uses an infrared technology that allows us to measure the quantity of blood flow going to the brain tissue, which is a proxy of neuronal activity. The combination of inertial measurement units and fNIRS provide us with a unique opportunity to understand the mechanisms underlying walking fatigability in people with multiple sclerosis.

What have been the most surprising findings so far in your research? Has anything challenged what you or the medical community previously thought about walking fatigue in MS?

That’s a tough question, as every finding is a piece in the puzzle and it has its own importance. But I would say that we have some preliminary findings showing a possible mechanism for walking fatigability in multiple sclerosis, where basically those who have more brain activity are those who have less walking fatigability. In other words, it seems that having a good capacity to activate the brain might mitigate the appearance of walking fatigability, but this still has to be confirmed in large-scale and longitudinal studies.

Looking ahead, how do you envision this research translating into real help for people living with MS? What might personalised rehabilitation programs based on your findings look like?

Our research has shown that walking fatigability is a very prevalent symptom in people with multiple sclerosis, where around 70% will present some kind of problem when they have to walk for a prolonged period. This basically indicates that when we treat walking fatigability, the rehabilitation approach has to be personalised based on which component of the person is impaired. For example, if one is presenting an increase in foot-drop when walking for long periods, the intervention has to focus on reducing foot-drop over time by exercising the ankle joint more or by providing some walking training.

Your Account

Your Account